The film business has an interesting relationship with morality. I’m not talking about the latest scandals. I’m going back to the beginning.

From the start, filmmakers have been widely regarded as entertainment’s most hyperbolic storytellers. Movies based on, or inspired by, actual events are usually embellished to maximize dramatic appeal. Clever plot twists mislead audiences. Great actors fool us into thinking they are someone else. It’s a multi-billion dollar game of make-believe, and its “anything-is-possible” nature is one reason why so many people want to get into it — and why so many of their moral compasses go haywire once they do.

Look no further than the time honored mantra of “Fake it till you make it.”

With all due respect to Aristotle and any cognitive behavioral therapists who might be reading along, the entertainment industry’s version of “Fake it till you make it” has little to do with acting virtuous and loads to do with BS. Folks think they can fake (i.e. lie) their way into, through, and out of anything. When it comes to breaking into the business, many fall prey to this mentality, chalking it up as an accepted part of the make-believe game. While I’m sure some have succeeded by faking it, or winging it, or by sheer luck, there are many more careers that either never got started — or were needlessly derailed — by unscrupulous behavior, a lack of preparation, or other detrimental bad habits that I’d be willing bet were formed as result of thinking, “It’s okay to make something up.”

How does this toxic mentality become justified? And how can it be prevented? Here’s one theory.

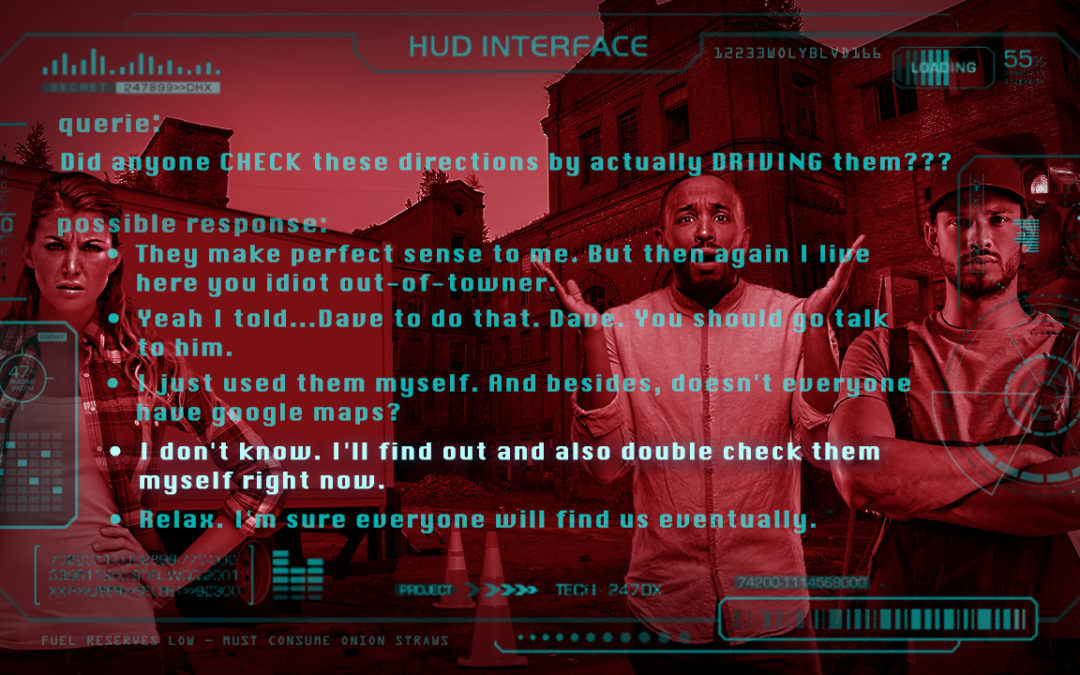

Production is intense. We regularly find ourselves in tight spots caused by challenging circumstances (the weather), difficult people (“I am a pescatarian you nimrod!”), or the dreaded, hugely stressful scenario of getting asked a question you cannot answer. That’s never fun. But when it’s a question you’re supposed to know the answer to, that’s worse (obviously). And if there are other people within earshot? Ugh. Embarrassing.

In these moments, especially early in your career, you tend to act impulsively. There’s pressure to respond immediately and always have the right answer. And in the cases where you don’t, you’ll find yourself facing an immediate, fundamental, and quite possibly instinctive choice:

Do you tell the truth or do you lie?

Will you acknowledge that you don’t know something or will you try to BS your way through it by being purposely vague (a lie of omission), making something up (a lie of commission), or blaming someone else (passing the buck).

The BS route does have some (short term) advantages. You avoid immediate embarrassment, and, if your lie is compelling enough, you might look like a hero.

But this is fool’s gold.

You might save face for a day or two, but unless you circle back and clean the slate, you’re actually taking out a very expensive mortgage on your integrity and reputation. For this incarnation of make-believe can rapidly become contagious. The more you get away with — exaggerating your expertise, misrepresenting a relationship, or overstating commitments — the tougher it gets to walk those lies back, the harder it is to differentiate between the actual and embellished. As the old adage goes, one upside of telling the truth is that you only have to remember one version of everything.

Ultimately, the only way out of your fib-fest will be to either get caught or to come clean. Depending on how long you’ve been disingenuous, you might be saying goodbye not to just a job, but also to friends, colleagues, and your reputation. So while indulging in a little BS might seem like an easy fix, don’t fall for the trap. Because lying about something always makes it worse.

I understand it’s hard to admit you don’t know something. especially in those moments when it suggests a real or imagined professional failing. But all professionals — in all fields — know that everyone makes mistakes, and it’s through that experience that true growth occurs.

That’s one of many reasons why the honest route is the better way to go. If you own your mistakes — and make a habit of not repeating them — you’ll earn the respect of your collaborators, and develop a reputation as someone who is genuine, and who puts the needs of the team before their own ego.

Besides, think about the flip side: If you never say “I don’t know,” then by default you a know-it-all. And when was the last time you met a know-it-all you actually liked? Or for that matter, who really did know everything?

I am not advocating that you go full Jeff Spicoli and adopt “I don’t know” as your go to answer. Success will have a very difficult time finding you if you are habitually unprepared. Aim to know all the answers, but accept the reality that it’s usually ok on those occasions when you don’t. Nobody came into this business knowing everything, and the more experienced members of your team will often be more than happy to share their knowledge with you as soon as they realize your are open to learning. And it doesn’t matter how old you or experienced you are, we all still have much to learn.

One final point: There is absolutely an element of hustling that’s required to succeed in filmmaking, especially the indie variety. Sometimes you probably will be better off begging for forgiveness rather than asking for permission. But pick your battles carefully or all that begging will get stale, and quickly so.

If you operate from a position of honesty and integrity, you’ll find that doing things the right way will get you the benefit of the doubt when you need it most. So the next time you encounter a question you honestly don’t know how to answer, embrace those three little words: ”I don’t know.” While tough to say, this response at a minimum suggests that you’re not full of BS, and should also buy you some time to go solve the problem.

Lunacy Productions’ head honcho Stu Pollard has helped produce dozens of independent films, including Alexandra Shiva’s documentary This Is Home (Audience Award, 2018 Sundance Film Festival), the powerful high school drama And Then I Go (2017), and Zachary Trietz’s Men Go to Battle (Best Narrative Feature, 2015 Tribeca Film Festival), as well as the rom-com Plus One and elevated thriller Rust Creek, both due out later this year. He has taught at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and Film Independent.

Good web site you have got here.. It’s hard to find good

quality writing like yours these days. I honestly appreciate people

like you! Take care!!

Thanks for reading. We’ll try and keep it up!