About Tamar Halpern

Tamar Halpern is a writer and director with nine feature films behind her — all produced for less than $1.2 million. We previously discussed her ventures in documentary filmmaking, and this week we focus on her work in TV movies, including her latest feature, Sinfidelity.

Lunacy Productions: How did you prepare for your latest project, Sinfidelity?

Tamar Halpern: Sinfidelity is loosely based on Fatal Attraction, so I rewatched that gem of a movie and broke it down by acts and sequences. Then I made a new outline for Sinfidelity to fix character and plot holes, and reduce unnecessary characters and locations (because we only had twelve shoot days). I also had to ensure we hit A&E’s nine required act breaks, and end them with the strongest thrill beats possible.

LP: What was the casting process like?

TH: I submitted a rewrite to the producer — now sort of a Fatal Attraction meets American Psycho with real, deep relationship complications — and he loved it so much, he wanted to play the husband! It would have been perfect, because he’s a really talented actor. However, he ended up producing two movies at once (if you can believe that superheroness!), so we were able to cast another great actor — Mark Jude Sullivan. The page one rewrite gave the main character a real drive and purpose that organically pushed plot, and that’s how we were able to cast Jade Tailor as the lead. She loved the character and the fact that the film was about the complications of relationships that happened to be inside a thriller.

LP: Can you tell us a little about the shoot?

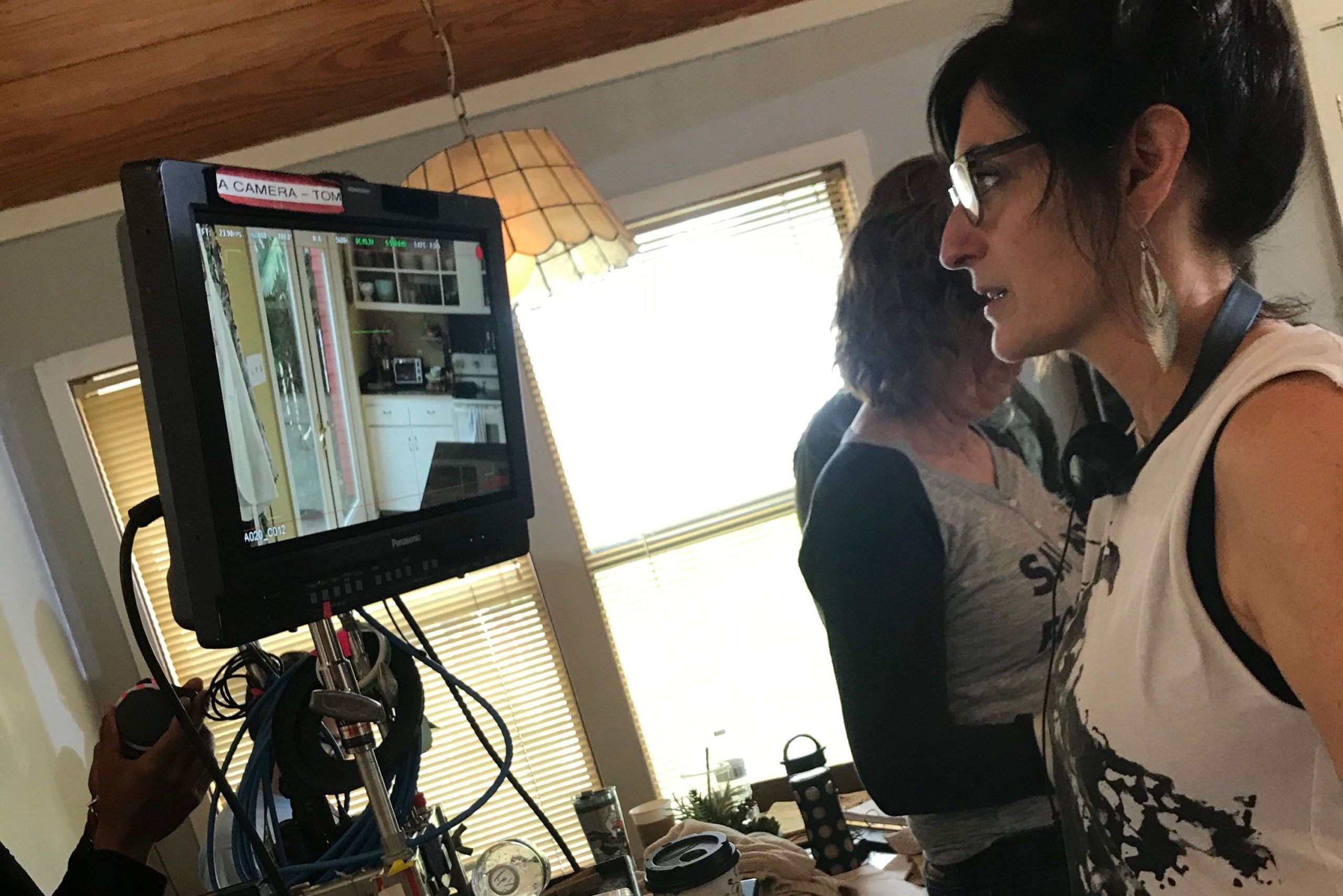

TH: We filmed in Lafayette, LA, home of some of the nicest humans on the planet. Our crew was from the New Orleans, Lafayette, and Baton Rouge communities, and we had a blast. It was a short shoot, but we were efficient. When making a 12 day film, you have to know which scenes are run and gun, and which you’re going to take your time getting just right. With me, there are usually a lot of scenes I want to take time with, so luckily my crew was amazing and made it work — stunts and all.

LP: How does the Lifetime system work?

TH: My understanding of Lifetime is that there are production companies — like Mar Vista and Reel One — who specialize in thriller and romance films made for lower budgets. They pitch concepts to some executives at New York Lifetime, and they either approve them straight away, or give notes as the script is developed. Lifetime tells the production company that if they can deliver the film within certain time and budget constraints, they’ll buy it when it’s done. Many of these production companies also have foreign distributors who they sell to. I suspect they may receive some pre-sale money there to help fund the production.

LP: Is there a formula to these stories?

TH: Definitely, but it’s always fun to get as creative as possible within the established rules. And each production company has a list of rules — I once received a list that included “No supernatural or lesbian stories.” Because these are considered TV movies, they follow a nine act structure, close to the eight sequences of a three act structure. We have a cold open. Something horrible happens that’s thematically related to the plot. It doesn’t necessarily happen to the protagonists; the antagonist could be responsible. Someone gets killed. Someone is thrown off a balcony or kidnapped. Then Act I begins and for 15 minutes, it becomes a Hallmark movie. Very fairy tale-like, some love, some domesticity, everything’s okay. Act I ends with what’s called a Thrill Beat, where all hell breaks loose to destroy this seemingly perfect world. Each subsequent act ends with a Thrill Beat, something that makes the audience stay tuned — a twist, a turn, a surprise, a scare, a murder, a close call. Generally, these films feature a woman who, through no fault of her own, finds herself in an untenable situation, and must react to it and actively correct it. There’s often a coda at the end of final act where either everyone’s happy and the problem is behind them, or it seems that way but we realize the characters are still haunted.

Tamar Halpern reviewing playback on the set of Sinfidelity in Lafayette, LA.

LP: How do you book a directing project?

TH: The production company reaches out. Sometimes the producers are hired by the production company. Sometimes the producers are the production company. It’s different every time. They’ll tell me they’re thinking about doing a movie in say, Louisiana. They give me the dates, which are usually less than a month away. If I’m available, they give me the deal terms, and I ask for a contract and the script. I read the script, breaking it down by act in outline form, then create a new outline. Once it’s approved, I start rewriting from page one.

I am often given scripts with three major problems — the women are one dimensional, the plot doesn’t track, and the dialogue feels pat. I work with the producers and the production company executives on my new outline and then, when everyone’s happy with the changes, they’ll say, “Great, can you turn the script around in three days?” Luckily my outlines are very detail oriented, ten pages or more. But still, I’m a human, so I tell them I’ll do my best. Once I arrive to wherever we’re shooting (so far it’s been Belgrade, Serbia; Albuquerque, NM; Louisville, KY; and Lafayette, LA), I have about two weeks or so to location scout, cast, and meet with my department heads. It’s a whirlwind but the people I work with are super-organized and professional. We all know what we’re doing, and if we don’t, a creative producer is there to pick up the pieces.

LP: Walk us through a typical day of shooting a narrative feature.

TH: I like being analog, because I don’t like to carry a lot of things when I’m working. I have my clipboard with my sides and shot list. A pen to track my shots. I often work with two cameras for speed. Because I rewrite the scripts, I know exactly how each scene will play out.

When I first started making films (before doing these A&E thrillers), I needed to learn how to create better transitions between scenes. Sometimes they work the way I’ve pictured them in my mind, but sometimes you need more. The more you shoot, the more you begin to see it like a symphony. Everything coming together, the perfect way in and out of a scene, so it flows.

The last four features were all 12 day shoots, mostly with two cameras. They were a circus. I have texts from my script supervisor tracking my daily setups. At first, I thought the numbers were over two days. She was like, “No, that’s today.” It was something like 42. That’s an intense day. But because we never do company moves (if we can avoid it — company moves cost an hour or two), some days can be much heavier than others. And on the “light” days, which we’ll often reserve for stunt days, we still end up cutting it close on time. We directors always want more time and more money, even on “light” days.

LP: For a feature-length script, that’s an aggressive page count per day. How do you stay on schedule?

TH: Right. Across twelve days, the average page count is a little over 8 pages. The production companies across the board require scripts no less than 99 pages. And the delivered film must be exactly 87 minutes. And thrillers often have a lot of B story and/or small scenes to keep the tension going. Those small, intercutting scenes can be far more time consuming than, say, a four page dialogue scene in a bedroom between two people. Usually, when I arrive on set, my DP and I will block with the actors and then send them to makeup and wardrobe. We discuss, and I’ll share any ideas I have, as will my DP. At that point we know exactly what the shots will be. If we have time during prep to discuss, that’s even better, but sometimes we don’t.

If I know I’m short on time, maybe we decide to do a oner. Really great with two cameras. Risky as eff with one, but sometimes that’s just the way it’s got to be. Because sometimes I need to split B cam into second unit. Speaking of, that must be discussed with your cinematographer first during prep — or better yet, before you hire him or her. Because we can’t assume that having an A cam and a B cam means we can automatically split them. Some DPs are not cool with that. Plus, you usually only have one sound team. I generally break B camera off to shoot scenes with no dialogue. It’s just this crazy math that you keep in your pocket just in case the clock is running out on you. Not everyone’s comfortable with it, but it has to be done on 12 day shoots.

That said, there are directors who approach these 12 days shoots differently than I do. They simply do establishing, single, single. No dollies. No moves. No two shots. And I get it. It’s a guaranteed way to make a movie in 12 days. But it’s not my way. I want to honor the script, the actors and the crew by making the best looking movie we can.

LP: In these cases, how do you assemble your second unit?

TH: If everything’s under control, I’ll send my first AD out to direct second unit. Otherwise, I’ll send a second AD, or sometimes the producers will just pick an assistant.

My B camera people are often really talented cinematographers who haven’t had an opportunity yet to shine as DPs. They’re just waiting for their moment, so when we send them off and they’re given some latitude, they take their chance to be creative. And when I see the footage later I think, “Oh my god, what a genius.” Then it becomes one of my favorite shots in the movie.

LP: How do you rehearse with your actors?

TH: We discuss during prep. We talk about scenes, we talk about subtext. Then, on the day, we block. But it’s also a chance to rehearse. We can make some adjustments there, honestly, at that point the actors are just going through the motions, hitting their marks, making sure they’re off book. They aren’t giving us the performance yet, just trying on the scene for size and shape. Sometimes, while they’re in hair and make up, I’ll visit to discuss anything about the scene I have on my mind. Actors are so fucking smart. They usually already know what I’m about to say. If they’re newer to acting, I’ll run lines with them while the crew is lighting, or while the actors are in makeup.

The actors come on set prepared. I like to see what the actors will do first. Then make adjustments. There’s a way to communicate with actors. Some of them can pivot really well. Sometimes they can’t and I have to pivot my expectations. It’s all a dance. But pro actors bring it. They bring it better than you can explain it. They read the script, too. And there’s a reason they work all the time. In these films, I usually get two actors as leads who have more experience than anyone else on the crew including me. Then the rest of the cast varies from semi-experienced on down. It depends on the actor. Having worked with a lot of kids and non-pro actors on past features, I’m ready for anything.

Tamar on set with the cast of Sinfidelity: Jade Tailor, Mark Jude Sullivan, and Aidan Bristow.

LP: Are you involved at all in casting?

TH: Very much, if possible. I’m really picky. But on these films, it’s a producer’s medium, so sometimes I’m handed people, and most of the time I don’t know them. Then I look them up, and they’re all great. Even the ones I might be initially nervous about. They’re monsters. They live and breathe it. They nail it with little to no directing needed. Sometimes they take it up a few ticks better than you ever imagined when you wrote the script. There’s not a lot of directing at that point. They are the character.

I have a lot of faith in actors. I used to be an actor a long time ago, and I have such reverence for them — how they embody what’s written on the page with their physicality, their face, their sensations and voice. Actors sense things. I’m big on making sure the actors know when I’m happy with them, because that makes them want to push harder and go deeper.

LP: How involved are you with the editing process?

TH: It depends on the producers and the production company. Your contract ends when you turn in the directing cut, and they might only give you a week to do that. They might edit and send you cuts for notes. Not my favorite. No one wants to do 15 pages of notes with time code via email. But it just depends. I have producers who have me there all the way through color correction and sound mix. Working with the composer, giving notes until it’s perfect. And I’m so grateful when they do, since the contracts don’t stipulate a director’s involvement past picture lock. Like I said, TV movies are a producer’s medium. On one film, the editor was in Canada and I was in LA and their Internet connection was useless, so I got cuts and gave notes. While editors are pretty good at reading them, you can pretty much forget it if you give it to the producers.

LP: Let’s switch gears a little. What is it like to raise a child while working as a filmmaker?

TH: My friend Lisa Muse Bryant is a writer. She has five kids, all under the age of 10. Her husband became a stay at home dad, because she was doing so well as a TV writer. Her mother moved in as well, so they had two parents in the house even when she was at work. Unless you have that kind of situation, I don’t really advocate having more than one kid if you want to be a director.

If you have a two-year-old and a five-year-old, their needs are completely different. They’re in completely different places in life, and it’s double the work trying to make them both happy, or happy enough so you can write, or direct, or go to work. If you really want multiple kids, maybe space them out 12 years or wait until you can afford a nanny? Or get your parents or your partner’s parents to move in, if you’re lucky enough to have that kind of support.

Having a partner helps a lot. In my case, my first husband and I separated when our son was three, but we maintained joint custody. I was at graduate school by the time our son was five. I worked at restaurants, attended classes, and was a mom, and I basically didn’t sleep much. If somebody had asked me at that time, “Are you happy? Are you feeling fulfilled? Do you think you’re handling it all?” I probably would’ve been said, “My god, no.” I felt like I was doing everything at 70%, because that’s the best I could do as a juggler.

My directing work started when my kid was a teen. I started film school when he was little, but I was hired for my first film much later. When I was hired for my first big movie (Jeremy Fink and the Meaning of Life), my son Jordan Halpern Schwartz was starting out as a composer after being in bands and playing music since he was tiny. When the producers told me we didn’t have a budget for music, I called Jordan up and said, “I need you to do this for me and for free.” And he did! Because he wasn’t paid, he kept the rights to the music and went on to sell the tracks twentyfold for commercials and other films. So my blatant exploitation of my own child turned out to be okay.

Tamar with actress Blythe Howard (as AD nick Johnson worries about making the day).

Thank you Tamar for giving your time and telling your story! We can’t wait to see Sinfidelity, premiering August 16 on A&E.