It’s hard to imagine Darth Vader striding through the corridors of the Death Star, the Man of Steel soaring over Metropolis, or a shark fin rising ominously out of the water, without also thinking of John Williams’ corresponding musical themes. An original score – music composed specifically for a film – can establish tone, subtly reveal character, and accentuate emotional impact. At their best, scores can become just as iconic as the films they originated in.

In this, the third installment of Lunacy’s practical guide to music in film, we’ll be talking about composers. Check out our first post for an overview of terminology and various music licenses, and see part II for tips on securing rights to pre-existing songs (including hiring a music supervisor).

What’s A Composer?

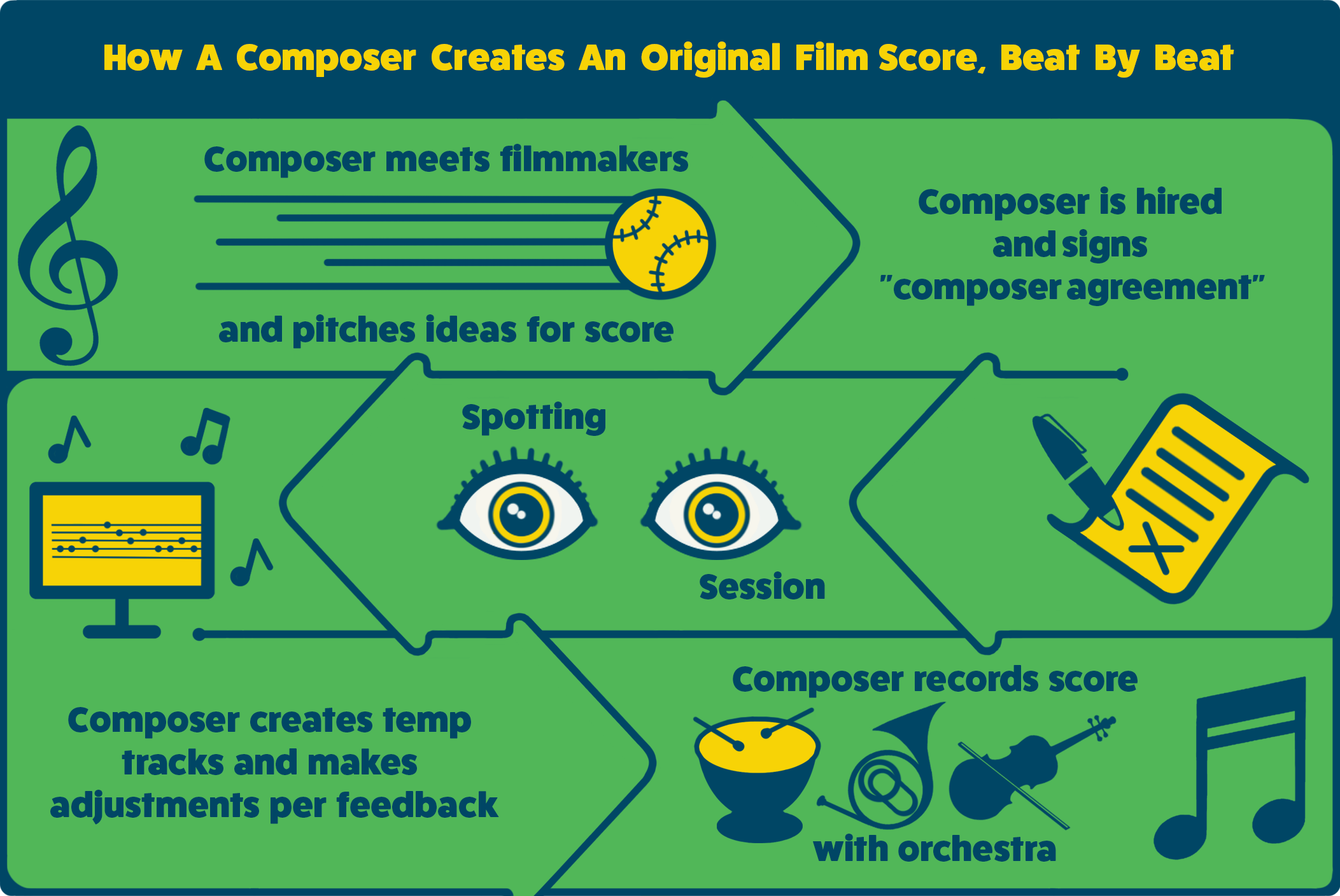

A film composer is responsible for every aspect of original music in a film. Beyond just writing and orchestrating the score, this includes building out a budget, communicating with the production team, providing temp tracks to the editor, holding spotting sessions with the director, and creating the final deliverables per his or her contract (cue sheets, performer agreements, and, of course, the final version of the score).

Hiring A Composer

In one sense, the composer begins working on the score for a film before they’re even hired. During the interview process, the director and producers meet with several candidates, trying to find someone who fits the tone, sensibility, and ambition of the project. The director might have a list of film scores, classical pieces, or popular music that inspired them or are tonally similar to the film. The prospective composer might pitch some general ideas about instrumentation or style. By the time they are officially brought on board, the composer often has a pretty good idea of the expectations.

The Composer Agreement

The composer agreement is substantively different from the deals other department heads sign because of the music rights involved. When negotiating a production legal package with your attorney, be sure that deal includes a composer agreement as it can not only be a complicated deal, but a lengthy negotiation. In addition to contracting for services that will stretch deep into post-production, this also serves as a licensing agreement (and/or a transfer of ownership) for the music the composer creates.

We can’t hope to cover every last aspect of a composer deal in this post – and this isn’t a substitute for legal advice (of course 🙂 ) – but here are some critical elements to be aware of:

- Services: The composer should be required to create the original score and the corresponding master recordings (“Masters”) as part of the deal.

- Compensation: What you pay your composer will usually consist of a fixed fee as well as some form of contingent compensation. This section should also note what specific costs the composer may incur that the producer is not obligated to pay.

- Credit: The composer customarily gets a single card in the main credits along with your other key creatives and main lead cast.

- Rights & Ownership: These are the most critical parts of the composer agreement.

Rights refer to what the agreement permits the producer to do with the music and should grant them broad power to use it however they want.

Ownership of the music is more complicated. Often the composer retains ownership, but savvy producers know to push for at least a share of the publishing rights. In some cases these can be worth a great deal later.

For a deep dive into composer agreements, including sample deal pages and much more information on why every producer should ask for a piece of the publishing rights, check out our extensive addendum here!

The Spotting Session

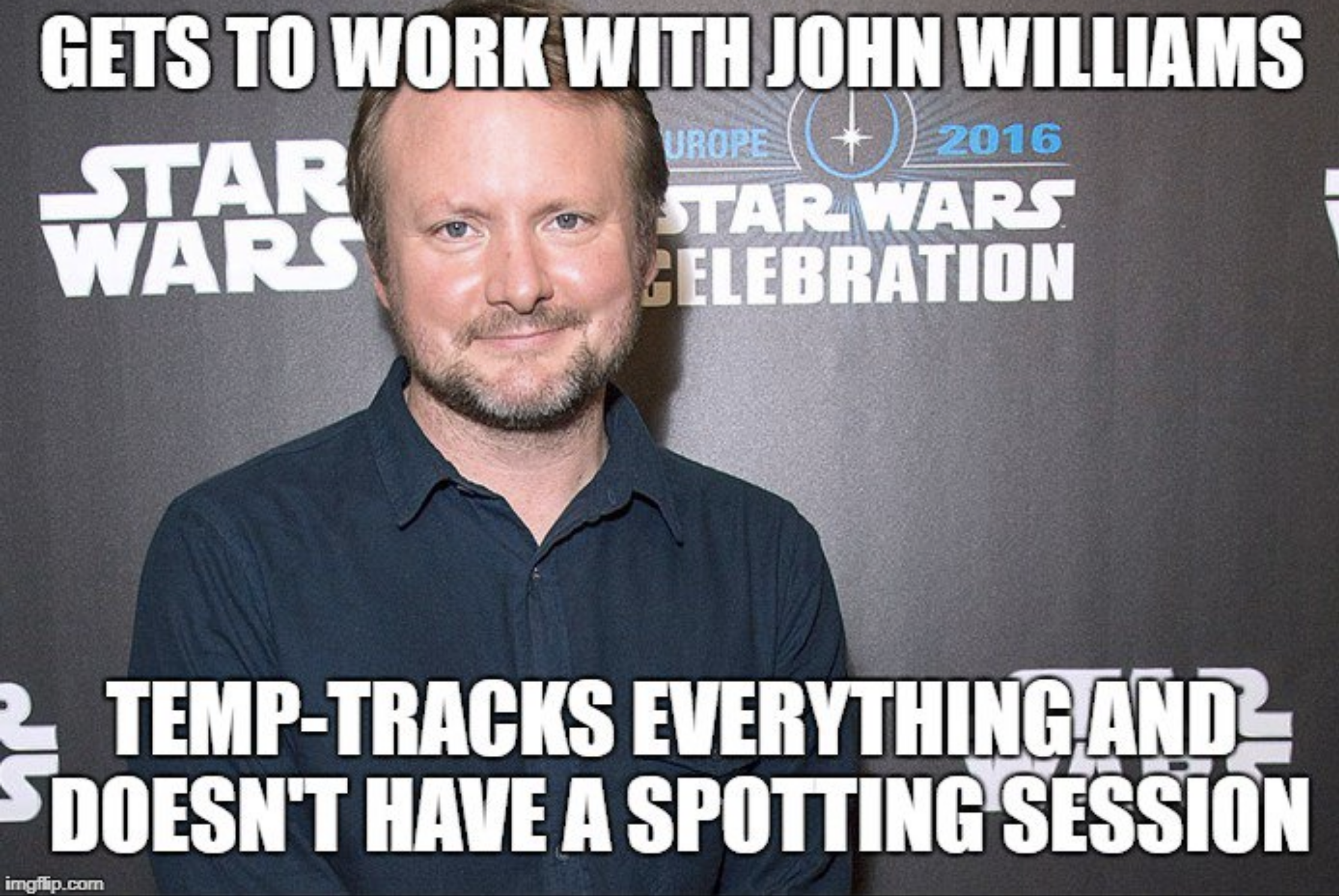

The composer’s job really starts in earnest during the spotting session, when they review a fairly advanced cut of the film with the director. Generally spotting sessions start by screening the film straight through without stopping, then screening a second time, pausing throughout to discuss where there should be score and what that music should convey. Spotting sessions can last for just a few hours or for multiple days depending on how much discussion is needed. Discussions can range from very specific notes on the style or rhythm of the music, to more general emotional beats (“This scene needs to be sad”; “This moment is triumphant”; etc). Ideally this is a collaborative process, where the director comes in with some specific ideas, but remains open to creative suggestions. A bad case of tempitis can really derail a spotting session.

Once the composer has their instructions, it’s time to write some music!

The DAW

A digital audio workstation, or DAW, is computer software (such as Logic PRO x, ProTools, or Reaper), that allows the composer to sequence midi parts, mix audio, use sample sounds, and create different instrumentation. With a DAW, a computer, and a MIDI keyboard, composers can create elaborate digital compositions. These electronic tracks will serve as temp tracks during the earlier stages of post-production. Don’t be alarmed if they sound a little cheesy, although digital samples of actual instruments keep improving in terms of approximating the real thing.

As the cut is fine-tuned the composer gets feedback on their work. By the time the film is picture locked, the composer will be in a great position to finalize the timing and arrangement of all the tracks, so any large scale recording sessions can be scheduled sooner than later.

Recording

On some micro-budget films the electronically generated tracks created by the composer might actually be used in the film. But there’s still an audible difference between a score built on a computer and one created by musicians playing real instruments on a scoring stage. That’s why most films, even those with very modest budgets, aspire to record their score with live players, whether it’s a minimalist vibe or a full orchestra.

The recording sessions for the score could end up being some of the most expensive elements of your post budget. Booking hours of studio time, plus the cost of professional musicians and capable engineers, is not cheap. That’s why so much care goes into spotting the film and reviewing cuts with temp tracks. By the time you get into the studio, you want to know exactly what you need.

Some Things To Keep In Mind…

Some movie moments just don’t work without the right score. Jump scares in horror movies, for example, almost all rely on some combination of aggressive score and sound design, and they fall very flat when you remove that. Big emotional payoffs also depend on the score to heighten their impact. The score can’t make a happy scene sad or a funny scene scary, but it can augment the elements that are already present. It isn’t meat and potatoes, but it’s essential seasoning.

On the other hand, sometimes silence says more than the score can. Wall-to-wall music can feel coercive and heavy-handed. Sometimes you don’t want to telegraph the emotional response you want from your audience. It’s better to let the performances do the work. And audiences can become desensitized to a film that’s scored too heavily. Don’t be afraid of silence; it’s also an invaluable tool.

As with the soundtrack, your score should never be an afterthought. It’s never too early to start seeking out talented musicians to collaborate with. It might take some time to find someone who matches your sensibility, ambition, and so forth, but these working relationships often last for entire careers (Spielberg/Williams, Coen/Burwell, Burton/Elfman, Nolan/Zimmer, etc.)!

That wraps it up for our overview on Composers, but we have more to come in our music series. Remember to check out the post on composer deals if you want to learn more about the nuances of that agreement, and don’t forget about our popular film music master class.